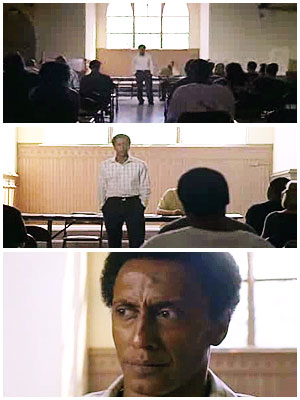

Season 1, Episode 3

D’Angelo tries to teach Wallace and Bodie the game of chess. ”This,” he says, kissing a piece, ”is the king pin, aiight? He the man.” The boys figure Avon for their King, Stringer the Queen, and the Castle the drug stash. ”These are the pawns, they like soldiers,” says D’Angelo. ”They be out of the game early.” All three boys are dead by series’ end.

Season 1, Episode 4

Watching Bunk, chomping on his cigar, and McNulty methodically work a crime scene was one of The Wire‘s richest pleasures. In the victim’s kitchen, their whole dialogue is one variation or another on a most satisfying swear word. Actors Wendell Pierce and Dominic West, brilliant both of them, make it sound like Shakespeare. Suck on this, network crime procedurals.

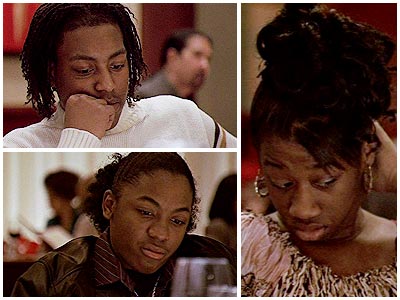

Season 1, Episode 12

Bodie and Poot, on Stringer’s orders, have to kill their friend Wallace. It’s a cruel death — all the more so because Wallace whimpers for the mercy of his friends — of a boy who made school lunches for the kids in his house and wasn’t fit for the corner. Wire fans were put on notice that their favorite characters were always vulnerable.

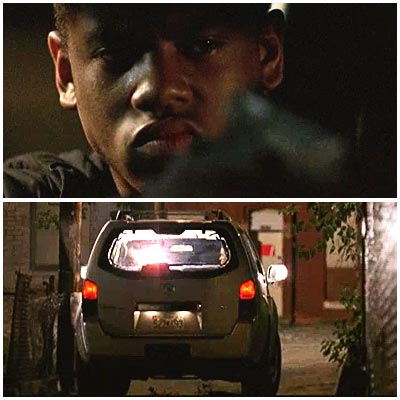

Season 2, Episode 11

Frank, a ruined lion of a man, scrambles to make a wretched mess right. On his frantic nephew’s urging, Frank drives to meet the Greek under the bridge to strike a deal that will save his son. The scene cuts from Frank smoking a cigarette, to a crooked fed, to the Greek getting a phone call, to Frank’s walk to certain doom. Awful stuff.

Season 2, Finale

The montages are what will keep you up at night. Every season ends with a jaw-dropper, but if forced to pick, you gotta go with this one, set to Steve Earle’s ”I Feel Alright.” From shots of the stevedores’ seal of brotherhood to drunken out-of-work men on the streets, from mournful Beadie to broken Nicky in the drizzle, it’s a killer.

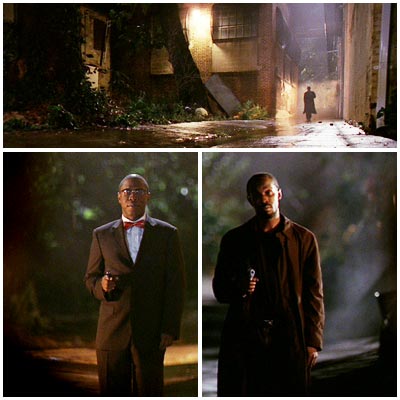

Season 3, Episode 11

Omar whistling ”A-Hunting We Will Go” down an alley at night is already magic. Cut to Brother Mouzone (or Bow Tie, as Omar calls him) appearing out of nowhere, ready for a duel. ”I admire a man with confidence,” says Mouzone. ”I don’t see no sweat on your brow neither, bro,” responds Omar. Men with codes.

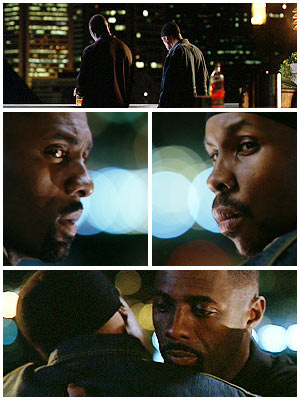

Season 3, Episode 11

Just a couple of old friends, brothers really, reminiscing over a good view and booze. ”I told your ass not to steal a badminton net!” Avon remembers telling Stringer when they were kids. The love flowing back and forth is really a goodbye, as Avon knows he’s setting his friend up. ”Us, motherf—er,” he says, hitting Stringer’s fist. ”Us, man.”

Season 3, Episode 11

Omar and Brother Mouzone, now partners, corner Stringer in his building, where he was supposed to at last taste business credibility. ”I ain’t involved in gangster bulls— no more,” Stringer swears, not realizing how wrong he is. Omar informs him of Avon’s betrayal. ”Well, get on with it, mothe…” Stringer says, and the two men take him out.

Season 4, Episode 8

Baltimore, from the accent on up, is every bit a starring character. When Chris and Snoop are trying to ferret out interlopers trying to take over their territory, he tells Snoop to ”ask a Baltimore question…like, Who Young Leek be?” Snoop doesn’t get his reference to local club music or the Big Phat Morning Show. ”You ain’t right, girl. The average Baltimore n—– gonna know all that s—.”

Season 4, Episode 9

Bunny takes a few corner kids to Ruth’s Chris as a classroom reward. The kids, thrown off by the hostess and hushed conversation, by the waitress bleating about chanterelles, swing from preening exuberance to alienation. Afterwards, Bunny uses Zenobia’s wind-up Kodak to take a shot of the restaurant awning, but the kids no longer want to be part of the picture.

Season 4, Episode 11

Fans can argue that a frustrated Carver beating his fists into his steering wheel is the real gut-punch. But the scene of him finding Randy in the hospital, stunned after the unnecessary death of his foster mother, will rattle your bones. ”You going to look out for me, Sergeant Carver?” Randy yells down the hall. ”You promise? You got my back, huh?”

Season 4, Episode 12

Dukie, the lamb of the series, is ripped from Prez’s classroom, where he mastered the computer and depended on the teacher for sandwiches and clean laundry. To thank him, Dukie shows up to school with a Christmas present, a pen set, in a sad gift bag. Prez, powerless, realizes the boy is bound now for the streets.

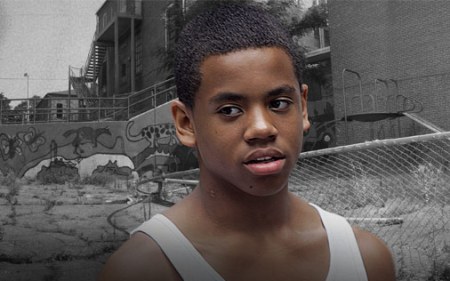

Season 4, Episode 12

Bodie, after working the corner since he was 13, realizes he’s an old man. The game has changed, and he can’t adapt his rules of behavior. ”Hell yeah, this is my corner,” he yells into the shifting night, knowing Chris and Snoop are coming for him. ”I ain’t running nowhere!” A soldier falls, with two shots to the head.

Season 5, Episode 9

Michael, realizing he’s fallen out of favor, pulls a gun first on Snoop. The woman, sociopathic in her bemused approach to killing, maintains the same composure in her final moments. ”How my hair look, Mike?” she asks, running a palm over her braids. ”You look good, girl,” says Michael, before he kills a woman he fears and respects.

Season 5, Episode 9

You have to clutch any moment of triumph to your breast on this show. Bubbles, after suffering mightily for four brutal seasons, celebrates his year anniversary of sobriety. ”Ain’t no shame in holding on to grief,” he says. ”As long as you make room for other things, too.” Remember that when you gear up for rewatching The Wire on DVD.